- Home

- Michael Boehm

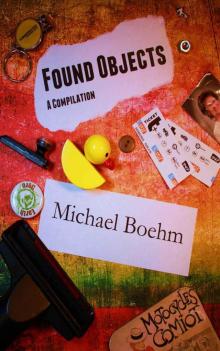

Found Objects

Found Objects Read online

Found Objects

A Short Story Compilation

By Michael Boehm

This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Found Objects. Copyright © 2013 by Michael Boehm. All rights reserved. Initially presented as Kindle Direct Publishing eBook. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book consists of a number of stories I developed with the guidance and assistance of the San Francisco Writers’ Workshop, and is dedicated to them. In particular, Tamim Ansary has been a wonderful resource for San Francisco’s budding writers. I also would like to thank my wife and daughter for their patience and support.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

IN GOOD TIME 5

MAESTRO 12

WHEEZE 21

MARGIN OF ERROR 33

Novel Excerpt: BURST 44

IN GOOD TIME

The town looked deserted, but Charlie knew better. Wiper blades thumped their rhythm as he rolled through town at a steady pace, doing his best to avoid debris strewn across the road. A stoplight suspended between two poles danced wildly in the wind, and Charlie accelerated through the intersection at the thought of broken power lines whipping and crackling across his SUV.

He stopped outside of the small clapboard house and sat for a minute, playing his eyes over the familiar sights. There was the tree he had fallen from as a boy. Around back he could see the rusty swing set, the chains oscillating in crazy patterns. Pulling the hood of his rain jacket around his head, he opened his door and stepped out into the maelstrom. The storm assaulted him immediately, horizontal rain stinging his cheeks as he hurried for the porch. The screen door was blowing back and forth wildly in the wind; seizing it with one hand, he thumped heavily on the front door with the other. After several minutes of pounding, his efforts were rewarded by a clattering that he felt through the wood as multiple latches were disengaged and bolts were drawn back. Finally, the door came open, and behind it stood a small, solid woman, her steel-wool hair fluttering in the breeze. She mouthed something that was completely lost in the howling of the storm, but seemed to begin with "Well I'll be dipped in..." Realizing the futility of speaking over the wind she gestured sharply for Charlie to come inside, stepping back to admit him before shutting the door with difficulty.

Charlie pulled his hood back and wiped water from his face with his hands. "Hi, mom," he said.

She stood there a moment, surveying him with a level gaze, a hand on her mouth, the other on her hip. Sighing, she dropped her hands to her side. "Let me take your coat," she said.

"We can't stay long," Charlie said. "I'm getting you out of here. Get your things."

She stared at him coolly "Nine years, Charlie. Nine years since your momma seen you last, and that's all you got to say? I don't know what passes for hospitality up north, but here when someone pays you a visit, you show them a little kindness. Now take off your coat and I'll make us some tea."

Charlie sighed and unzipped his jacket.

They sat in the parlor sipping Earl Grey as the wind howled outside. The ancient oak tree scraped branches against the window as Charlie fought to control his anxiety. Every instinct told him to get out now, to bundle his mother up under his arm like a football and make a break for the door before the full force of the storm smashed the little house to pieces. "Momma, it's a hurricane," he said.

"Been through plenty of ‘canes, I have," she said, glancing at the window. "She's coming on strong, that's for sure. And she's angry. But I think I'll be fine."

"Have you seen the satellite pictures?" Charlie asked. "It's headed right for here. It'll make landfall in a couple of hours, and the storm surge will be well over the levees. This whole town will be gone tomorrow."

The moments ticked by as Charlie watch his mother calmly sip her tea, carefully lifting the cup to her thin lips and slurping. At the best of times that annoyed him; now it pushed him close to a berserk frenzy. He listened to branches scratching on clapboard siding while his impatience grew. Without looking at him, she said "So how come you never called after the funeral?"

Charlie lowered his head and steepled his fingers before his face. "Things were crazy, momma. I was doing my internship at Stony Brook, pulling ninety-hour weeks. Janet and I had just bought a house, and...”

"How is Janet," she asked. "I notice you ain't got no ring."

"We divorced, momma. A couple of years ago. It didn't work out."

She closed her eyes and lowered her face. "She was a fine lady. What happened?"

"We didn't have enough time together. She had her residency, I had mine. Between that and my research assistantship, and her volunteering, we hardly ever saw each other. We would sneak off for a weekend once in a while but it was like we were strangers on a first date every time. It was awkward and exhausting.”

"Time's a funny thing, you know?" Charlie's mother said. "It's the one thing you can never make any more of. You can borrow it, save it, or waste it, but you can't make it fresh. That's why it's the most valuable thing in the world. We all get the same number of hours each day. People say ‘I don't got time for this,’ what they're saying is they got other things they'd rather spend their time on. We all got the same amount, Charlie. We just gotta choose what we do with it."

Charlie picked up his teaspoon and stirred his cup. "I'm sorry about dad," he said. “I wish I could have done more.”

His mother cocked her head and narrowed her eyes. "Is that what you think this is all about? Charlie, did you think I blamed you for that?"

"I should have seen it," Charlie said. "I'm a doctor, after all. After he died, I just-"

"You what?" his mother shot back. "You what? You felt guilty, so you hid in your condo in the city? You blamed yourself for it and because of that, you decide to punish everyone around you? You don't talk to me, you leave your wife, you forget your family? What kind of man are you?"

"I have a life!" Charlie shouted. His spoon rattled on the formica. "People respect me. I save lives. I write articles that people read all over the world. People ask me to speak at conferences. I'm making a difference. Dammit, momma."

His mother gazed at him coolly. "We all have a life, son," she said. "You think you're a big shot, but you can't even take care of your family. Now you roll up here in your ess-you-vee and think you're gonna make everything all right just like that. In all your trying to be someone, you forgot who you are. Let me ask you something. When you go to these fancy conferences of yours, and someone asks you where you from, what do you tell them?"

They stared at each other across the table, the entire house shuddering. A window exploded inwards as a branch shattered it. Gossamer curtains whipped about as sheets of rain, splintered wood, and broken glass sprayed in. Charlie jumped up and seized the branch hanging halfway into the living room, trying to shove it back outside. "Momma, it's time to go!"

She stood up, clutching at her shawl. "I'm not the one looking to be saved, here, son!" she said. "I've made my peace."

Charlie heaved the branch back out the window and turned to look at his mother, holding one hand up to block the storm. "Please, momma," he said. "Please. Let me take you somewhere safe."

They stood there, staring at each other as the rain dripped off their faces and the winds whipped about them, tearing the room to pieces, swirling the jetsam of her home about them.

Charlie drove out of the town, headed north on the levee road. The storm rocked the heavy vehicle, and when the rain wa

s heaviest, he could see no more than a dozen feet ahead. Slowly, carefully, he drove down the centerline of the road, the water three inches deep as the storm surge began slopping over the levee. Twice he had to get out and drag debris out of the road, and both times the wind nearly knocked him down. Now up ahead, out of the grey he could just make out the shape of the trestle as he approached the bridge. He breathed a sigh of relief when he saw that it was not yet inundated. Stopping the car for a moment, he glanced back in his mirror at the town he had grown up in. The town looked deserted.

"Don't be stopping now, son," his mother said to him from the passenger seat. "This levee is coming apart."

Charlie looked over at his mother, sitting proudly in her seat. A slight smile played across her lips. "Sure thing, momma," he said as he eased the vehicle onto the bridge and headed north.

MAESTRO

The city was shattered. Tumbledown buildings leaned together like drunkards, whispering secrets from vacant office to moldering apartment. Lonely breezes slipped down streets, choked with the charred corpses of automobiles.

The Maestro carried his duffel bag down one street, weaving his way among piles of crumbled masonry. He arrived at last at the symphony hall, its squat marble architecture largely intact, save for the shattered windows and ripped façade. He withdrew a key ring from his pocket and unlocked the side door, as he had every Sunday at noon for the past eight months. Before that, he entered by the performers' entrance in back, but the sight of the bodies had driven him to the side entrance since then.

By touch and memory he wound his way through dark passages to the concert hall. He pulled the curtain aside and stepped onto the orchestra's stage. It was lit only by the pale sunbeam filtering in through the rent in the roof, but it was enough.

He unzipped his duffel bag, withdrew the portable stereo, and placed it on the stage. It was an old model, battered but serviceable. He breathed a silent prayer it would last through one more performance, and then withdrew a sheaf of music from the duffel bag. He placed the music on the stand, stood in his position on the podium, took up the baton on the music stand, raised it high, closed his eyes, and waited.

When he was ready, he slipped his free hand into his pocket, withdrew the remote, studded the Play button, and slid it back into his ripped tuxedo trousers.

After a few delicious moments of anticipation, Mozart's Quintet in E-flat for piano and winds, K.452 began to roll forth from the speakers. The Maestro swooped and bobbed his hands in accompaniment to the extended largo opening of the piece. He particularly enjoyed this performance, recorded at the Boston Symphony Hall in 1956. The piano was strongly in charge, but in an open and insistent, rather than forceful, manner. He metronomed his baton back and forth with the gentle and textured larghetto that followed. The woodwinds finally asserted themselves, as he knew they would. His chest swelled with the beautiful symmetry of the piece.

Far back in his mind, the small portion of his consciousness that was not swept up in the piece took note of the presence of the Wolf. He stirred, somewhere in the balcony terrace, stage left. The Maestro heard his hob-nailed boots scraping and thudding against the dirty floor of the balcony. He paid the Wolf no heed, however, as Mozart's allegretto finale swelled. He extended his baton towards the appropriate quarters of the orchestra for each instrument's cadenza passages. It finished with a flourish, and the Maestro added his own with a flick of his wrist. .

The music ceased, but the Maestro kept his eyes shut, hands lowered, breathing steadily. He could no longer ignore the Wolf. The man in the balcony pulled open a long zipper. He had never seen him, but the Mastro felt that he knew the man. The Wolf had lived in the balcony for a very long time now, and the Maestro wondered when he would tire of the Sunday music. When he did, the Wolf would probably kill him. It mattered not to the Maestro. The music was his life, his soul, the only thing worth living for in this wasted place. Without it, he would rather be dead.

The next piece flooded out of the speakers: Dvořák's No.9 in E minor. The Maestro swept his arms out and around in a strong gesture, and the Wolf was gone from his mind again. He gesticulated aggressively, enunciating the New World riffs of Dvorak's piece with his baton. The swells of music rose to the perforated ceiling, and the Maestro's soul rose with it, longing, questing, straining for apotheosis. There was something more here, something hidden within the music, something he had spent his lifetime straining for, always one note away. He reached outwards with his hands, trying to embrace the music, press it to him, become one with the modality.

With a sputter and a crackle, the music ground to a halt. The Maestro was left standing in mid-gesture as the last echoes of Dvořák resounded through the concert hall and died out.

The batteries. He had found them in the ruins of a convenience store, under piles of cheap sunglasses and shattered bottles of inexpensive liquor. They had lasted through six weekends, but he knew their time was due. Batteries were becoming harder to find in the blasted city, and these might very well be the last.

He lowered his hands, slowly, sadly, an angel coming to rest one last time before Revelation. He breathed once, twice, caught a sob in his throat. He had come so close. Close to absolution, close to ascension. But the world had pulled him back down again, into the mere dust.

His ears were excellent, tuned by a lifetime of practice. He heard it clearly when the Wolf opened the bolt-action of the rifle and slid the 30-06 bullet into the breech.

So this is how it ends, he thought.

It was appropriate that the end of his life should coincide with the end of the music. He chuckled a bit, until he heard the bolt slide home as the Wolf worked the action of the rifle. The Mastro did not open his eyes. He did not want to see the yawning black muzzle of the rifle pointing at him from the balcony. It would be a vortex of despair, consuming what little grace and dignity remained in the world. These things were anathema to the Wolf, and he could not stand them. This was his world now, and he decided what would exist and what would be obliterated.

The door opened.

The Maestro opened his eyes and was blinded by a rectangle of light at the far end of the concert hall. Two figures were silhouetted in the light, leaning together. They moved into the concert hall, and the Maestro realized it was one person carrying a large instrument case.

The Musician limped down the aisle towards the stage. She was a petite woman of golden complexion. As she drew close, the Maestro could see the reddish splotches on her face. Her hair was matted and shorn. One leg of her pants displayed a large blood stain near the knee. But she held her instrument case in a tender and proud manner that he recognized immediately. He nodded to her.

She laid the case gently on the dusty carpet, unlatched it, and withdrew a cello nearly as large as she was. She took her instrument to the first cellist position, sat, and rosined the strings. When she was done, she leaned the cello against her shoulder with one hand, and held the bow in her lap with the other. It was clearly a well-practiced gesture. She looked up at the Maestro with eyes calm and focused.

The Maestro hesitated for only a moment. He knew what they would perform. There was really only one appropriate choice. He placed his baton on the music stand, stepped down from the podium, and walked to the grand piano. He sat on the bench, looked back at the Musician, and said one name.

"Messiaen."

She acknowledged him by raising her bow and readying it across the bridge.

He plunged into the first movement of Quatuor pour la fin du Temps, deeply, soulfully. He knew it by heart, and he knew she would, as well. He imitated the clarinet's notes as best he could with the piano. He released a halo of trills towards the rafters of the concert hall, and the Musician picked up the bass notes with her cello, playing the fifteen-note continuous melody that underpinned the music. The piece had a sense of timelessness and melancholy that had always appealed to the Maestro. Now it was all that was left, the only thing between them and the abyss.

They began t

he second movement on an energetic note as the Angel of the Apocalypse released his triumphal sound, rending the world with his sacred trumpet-blast. They worked together in perfect synchronicity, piano and cello, point and counterpoint. The Maestro was lost in the music again, his soul soaring out beyond the crumbling symphony hall, out beyond the constraints of the ruined city, well past the mortal bounds of the flesh. A far distant part of his mind waited for the bullet that would end it all, knowing he would feel nothing except the glorious sensation of his soul merging with the music, his consciousness escaping into the far corners of the world with a triumphal shout, a rich adagio rolling through the planes of existence past the firmament. He was complete, he was full to bursting of life in this city of the dead, ready to refill it with spirit and power and grace.

They were in the fifth movement by now, the cello and piano duet, each playing true and straight. The warm notes of the cello solo magnified the love and reverence of the power of eternity, the eternity that at this very moment opened before them all. The notes were not of fear, nor of resignation, but of acknowledgement of the truth of life and the power of the spirit. Here, on the very precipice of existence, they conversed on the mysteries of the universe in three-fourths time.

The Maestro gasped and took a deep breath. He looked around, stunned, to realize they had completed the piece. He was exhausted and his hands shook, but a power rang in his head. With unsteady knees he stood, pushing the bench back, and turned to the Musician. She stood as well, facing him, cello already secured in its case. He nodded to her, and she returned the gesture. She turned smoothly and walked back down the aisle to the door, disappearing in a brief, brilliant rectangle of daylight.

The Maestro turned to the balcony, hands clasped peacefully before him, eyes downcast, ready for judgment. He waited several long moments before there was a report. A sharp, loud sound made him flinch. He was surprised how painless it was. There was another report, and another. They began to roil together, coming faster, stronger.

Found Objects

Found Objects